- Current title: National Science Foundation (NSF) Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology

- Location: University of Minnesota

- Field of expertise: stream ecology, microbial ecology of glacial-melt streams, glaciers and periglacial environments, and traditional ecological knowledge

- Website: www.heatherfair.com

Introduction: Someone took a bite out of my cookie

I was born with a bilateral moderate-severe mid frequency sensorineural (MFSN) hearing loss. This type of hearing comprises 0.7-1.0% of sensorineural hearing losses in which high-frequency (descending) and pancochlear (flat) hearing losses dominate. MFSN is described as the u-shaped audiogram or cookie bite hearing loss because sounds in the mid frequency, or spoken range are affected, with an audiogram that looks like a bite has been taken out of a cookie (Figure 1). Cookie-bite losses are virtually all genetically acquired, whereas aging and noise exposure are the most frequent causes of high frequency hearing loss. This link is an auditory example of what it is like to hear with a cookie bite hearing loss.

Figure 1. A mid frequency sensorineural hearing loss audiogram. The horizontal lines from 0-20 represent the decibels of sound that the average hearing person is capable of hearing. The curved lines denote the decibels of sound in which an individual with cookie bite hearing loss can hear in the right (A) and left (X) ears. This type of hearing loss occurs within the human spoken range with many sounds important for speech recognition masked by the hearing loss (e.g., p, h, g, ch, sh, f, k, s, a, r, o, and th).

As an ecologist, I think of people who are profoundly Deaf, those with a reverse slope hearing loss, a cookie bite loss, or deafness from a young age, as a rarity within the tremendously diverse field of ecology in which all individuals play an important role in the human ecosystem.

Without hearing diversity, we are missing the tremendous collective power of different human experiences, ideas, and creative thought which is shaped by information that our ears and eyes take in and interpret throughout our lives.

Tell us about your background

I was born and raised in a small Amish community in northeast Ohio where my Amish great grandparents were forced to leave the church due to their furniture business. My grandpa (who spoke Pennsylvania Dutch), dad who was a mechanical engineer (who I suspect had a cookie-bite hearing loss), mom (educator who worked with people with disabilities), and brother owned and managed the store. I lost my parents at an early age and the store has since become a brewery, which is pretty neat as I am a hop grower myself.

At the time I was born, infant hearing tests were not standard, so I was not diagnosed with my congenital hearing loss until around the age of eight. I was also diagnosed with severe near-sightedness at the same age. When my family was at our farm one day, I asked, “what are all the people doing standing on the hill?” What I thought were people were actually cows. I was taken for my eye exam where the big E was a blob and I got my first bottle-thick bifocal glasses.

As much as I hated my glasses, reading became enjoyable and I excelled at creative writing by using my imagination – because, hearing fatigue set in for me after the first few minutes of a class, and I was able to take a trip into my mind. During these trips, I was terrified that the teacher would pull me back into the classroom by asking a question that I wouldn’t know how to answer, so I tried to remain as inconspicuous as possible.

During my first hearing exam, I remember the doctor explaining hearing aids to mom but when technology limitations for cookie-bite losses and cost were discussed my mom’s expression guided the doctor’s response. He waved his hands and declared, “don’t worry, she’ll figure it out!” That’s the last time my deafness was discussed. We have to remember that back in the 70s; the concept of accommodations did not exist. Assuming an 8-year old would figure out what accommodations were and then apply them to her life was a monumental task.

My most vivid recollection of kindergarten was at the final bell of the day, when the principle announced “it’s time to line up outside at the buses”. I would put my head in my arms and cry in fear as this meant I had to figure out which bus was my bus number and read invisible lips when I was off track. I was terrified that I would end up at the wrong end of the county instead of home!! Could I have benefited from sitting in the front row in classes and obtaining notes from others? Absolutely! From cued speech? Oh my, this would have been a game changer for a cookie-biter in a hearing world! Learning ASL at a young age? Absolutely!!!

Looking back at my life up through mid-career when I finally got hearing aids, I’m amazed how I was able to stumble through life by reading lips, speech-guessing, expression reading, and avoiding burdening people by asking them to look at me and repeat. What I ended up doing was to laugh or to nod my head with a “yah” when the overwhelming effort to figure out what was being said exhausted me. Therefore, I suspect people had an impression of me as either scatter brained or very agreeable. No one knew I had my deafness because I, myself, didn’t realize I had a credible issue because as the doctor said, I could “figure it out”.

How did you get to where you are?

My road to becoming an environmental scientist was circuitous. The wonderful advice instilled by my parents, “you can be whatever you want” is something I hold very close to my heart. With my upbringing in a family business, business was the option I knew I could earn a living regardless of my passions, of which I had many.

I spent summers in the nearby creeks and loved raising cows, guinea pigs, dogs, cats, parakeets, and a donkey, but I didn’t know that ecology/environmental science could be a career. Besides playing first base in little league and punt-pass-and-kick with the boys, my first strong interest beyond writing was in playing and arranging music. I played piano, trombone, trumpet, French horn, and e-flat alto, and later learned violin while I was getting an MBA. No auditory words necessary with these pursuits.

Whenever I had a passion to learn a new instrument, I headed to the little barn behind our house and practiced for hours. Defiant! No one was stopping me from switching from trombone to trumpet! When I saw the Ohio State University Marching Band perform my sophomore year on a field trip, I decided this was the band I wanted to be in, so after high school I picked up an e-flat alto and painted 22.5-inch separated lines down the driveway to perfect the military-style high step. Highly competitive, I made it into the band my freshman year and every successive year. While around this creative group of musicians, I was amazed at how they could belt out crass jokes and sing lyrics to pop, rock, and looney tune hits! How did they hear all those words? I also was bestowed a nickname in the band that I won’t divulge, but I’m sure there is a direct correlation with my cookie bite hearing loss.

I had considered a career in medicine but my first attempt at chemistry sitting more than 10 rows away and to the right side of the lectern with a heavily-accented Russian chemist lecturer in a 500+ student lecture hall, did not go well. I decided I would rather work outside than in a hospital anyway, so I should find a career where I could travel. So, I went the practical route and chose international business management and marketing with an almost-triple major in Chinese. My ear guided my choices. Plus, I had no concept of environmental science or ecology as a career.

For my language requirement, I arrived at the packed 102 Spanish class and the only way to remain anonymous was to slink into the very last seat in the long line-up of desks. I couldn’t understand a word the teacher said from that distance. I thought, “wow, my Spanish sucks” and promptly dropped out. That quarter I found out that the university had 1-on-1 Mandarin Chinese language courses. I signed up for 3 credits, no pressure, self-paced. The experience was phenomenal and I continued to take Chinese classes through the graduate level over the next two years. I just had the feeling that China would become a super power in 20 years. My fortune was that not many students were signing up for Chinese language classes at the time so there were only five to six students per class. This was perfect – to sit around a small table so I could read faces and hear enough.

Fast forward to my corporate career at Wal-Mart HQ in Bentonville, AR with fresh MBA in hand in the information systems and global procurement divisions as a business analyst and strategist. I was able to use my Chinese and trained suppliers and associates on business analysis systems that we developed in Bentonville – all over Asia (China, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong), Brazil, Hawaii, and Dubai. My career was phenomenal and the trajectory was headed upwards, but I ended up having six different managers within seven years which didn’t allow enough time for advocacy-building and mentoring relationships to blossom. I never mentioned my hearing, and at that point I still didn’t have hearing aids because the issue had been buried since I was eight. I’m sure others noted something different about me….and they probably weren’t aware that I saw their subtle facial expressions when they thought I wasn’t looking. But I was phenomenal at putting cross-disciplinary teams together and generating ideas to solve complex problems. I worked with others to figure out innovative ways to weave systems and business processes together to cut down the lead time from product development to purchase order creation. The rest was for the logistics team to handle, which they did spectacularly.

I was in Hong Kong on an overseas assignment when 9/11 occurred. At one point after returning stateside, I provided a flow chart that was shared by my IT managers with the US government that helped them to understand how Wal-Mart efficiently collaborated with suppliers by supplying data freely. They had noticed that after 9/11 the stores closest to the trade towers were able to maintain adequate dog food supplies for rescue dogs, even when the rest of the country was at a stand still.

The last six months before I took a leave of absence I was an initiating member of the China environmental team that examined climate change and product life cycle issues, and I developed a balanced scorecard for executives, put together a green bag luncheon series, and was active in several other environmental working groups. At the same time, I was pigeon-holed into an accounting position (that was never on my career goals statement!).

My career goal was to become an international executive but during a career development meeting a VP told me, “but women usually stay at home and raise the kids”. I’m convinced that the time-lag it took me to hear what he was saying, which shocked me into silence upon realizing what he said, saved his pretty face. Wow, how did I let someone get away with that comment! I didn’t even have a husband or kids! At the time, most expats were married males with at least a kid or four to put into private schools while overseas. What a bargain they missed overlooking talented single females, but then, we didn’t look like leadership so we didn’t fit the profile.

At that time I decided that if I was not traveling, and I loved the environmental issues so much, how would I become a VP of global environmental sustainability without a science background?

I packed my bags and headed back to the university on a leave-of-absence, and my first NSF fellowship a year later sealed the deal. I was able to cut the umbilical cord from the corporate world and I’m forever grateful to the OSU Chinese Dept., my master’s advisor, and the National Science Foundation. I am thrilled with that decision because when you are so deep into the interests of the billions for pennies, and under stress that makes you sick, you lose sight of what is really important in life. I was appalled when I considered the pollution emitted from China factories directly into the atmosphere and aquatic environments, and flip flops and plastic beach balls that sold for a dollar but remained in the environment for thousands of years, all in the name of low prices for Americans.

Enough was enough; I had to learn how natural ecosystems worked before anything. You lose track of yourself, family, and the living environment when you are in the corporate rat race. I was once termed a “butterfly” because I networked with corporate leadership and the hard-working busy bees to brainstorm solutions, but now this butterfly was ready to migrate. I’m so glad I let my VALUES and magnetic compass guide my second career.

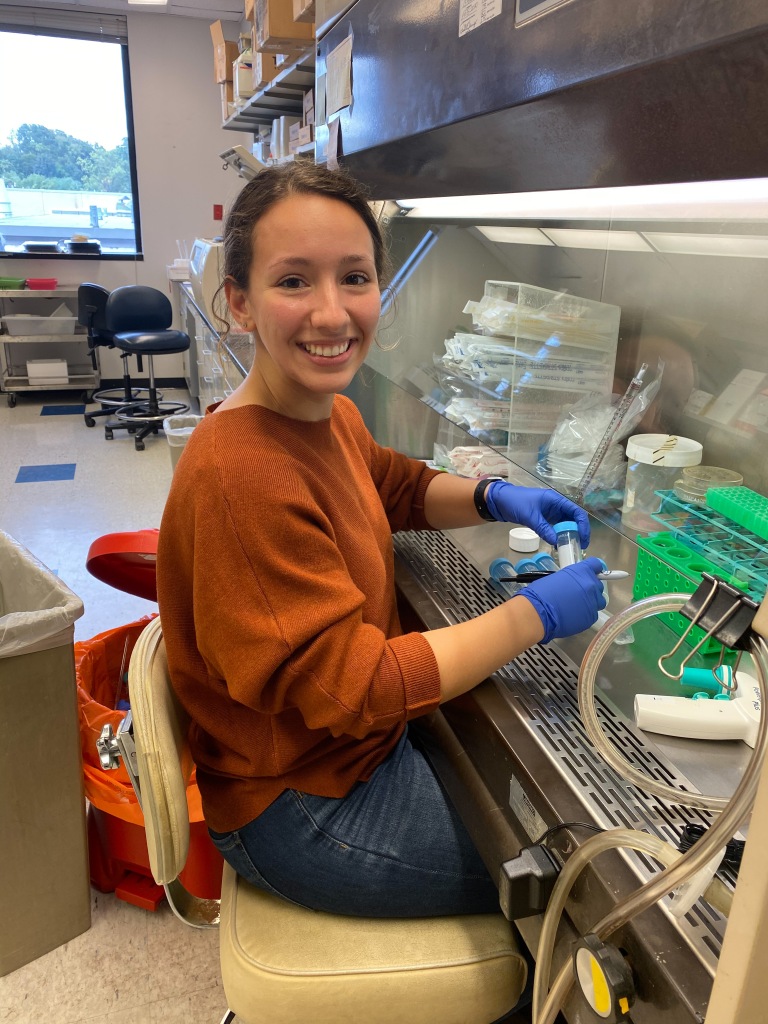

While in graduate school I spent half of my time conducting stream ecology research in mountain regions and glacier-melt streams in a small Tibetan village in the Three Parallel Region of SE Tibet. I acquired my first pair of hearing aids around the second year of my Ph.D. I went to an audiologist because my roommate that summer mumbled constantly and it was driving me crazy. When the audiologist, with his thundering New Zealand accent asked me “now how are you going to become a CEO with those ears”? I realized I really needed help. With my hearing aids, music suddenly had a third dimension, and I heard rain drops, keys, footsteps, book pages fluttering, key board tapping, and many other sounds for the first time.

My hearing aids helped tremendously, but they are not like putting on a pair of glasses. It takes time to retrain your mind, and it will never be as good and immediate as a pair of glasses but they can be a game changer if you give your mind time to comprehend and adjust to what you are hearing. I completed my Ph.D. in 2017 and am currently an NSF postdoctoral fellow in biology conducting supraglacial microbial ecology research. I was a Knauss Fellow at US Geological Survey, taught at Middlebury School of the Environment in China, Kenyon College, and Ohio Wesleyan University, and have mentored many students.

What advice would you give your former self?

This is actually a reminder to my current self to advocate for policy change and insurance coverage for hearing aids (in particular for congenital and disease-caused deafness). Why does a graduate student/terrified teaching assistant need to pay ½ of her low-income stipend for six consecutive months to cover a tool she needs to be able to perform her job (e.g., hear student questions, gain confidence in the classroom, pick up ancillary information, network with other graduate students, hear lectures)? For those who have a hearing anomaly that requires the most up-to-date technology, we should consider providing new hearing aids at least every 5 years, and more frequently if there is a radical technology breakthrough. After 10 years of daily use and tender care, my first pair wasn’t doing a thing. I didn’t realize this until I got a new pair. This should be considered for the future health and competitiveness of our nation. Additionally, training for all Americans to understand the issues faced by those who are profoundly Deaf and those who live with deafness would help in creating an inclusive and understanding country.

Any funny stories you want to share?

Before hearing aids, I constantly performed mental gymnastics to figure out what everyone was saying because what they were voicing seemed nonsensical. If I could remember everything my mind first “heard” I could be a stand-up comedian. Even with hearing aids, misunderstanding words is a frequent occurrence because hearing aids can never solve the ear-brain connection, although they can greatly reduce the time lag to solve the puzzle.

When I was heading to the gym one day, listening to NPR in the car, Ann Fisher was talking about eating bacon as a huge problem affecting young people, and I wrestled with this for a couple of minutes trying to figure out why young people eating bacon was currently such an issue. First, young people don’t typically get atherosclerosis, and since when did bacon become such a hot food item? Then it suddenly came to me — she was talking about vaping! Aha, now that made sense.

The irony about all this is that as everyone’s hearing is on the decline with age, mine will probably be the best at age 90 because with every few years, the technology to support cookie bite hearing losses becomes better. I heard new sounds with my second pair of hearing aids, and practically ran for cover as I heard “Pterosaur screeches” before my mind converted them into black bird caws. Imagine what I might be hearing at age 90.